How an icon comes to life

Whether an icon is canonical, it can be considered from the theological or painting point of view.

The theological aspect is the accordance of what the icon shows with the message of the Holy Scripture and the Christian tradition. The painting canon sets the technical rules we use to paint the icon. The basics of this method predate Christianity and are passed on from generation to generation. The iconographical canon does not limit the artistic freedom of a painter, it does not however – according to the Tradition and Church teaching – allow for too subjective approach to the topic.

Traditional pigments, gold and ages-old technique.

1. Panel

The panel has a special place in iconography. It symbolises the Tree of Life from the Garden of Eden and the Cross on which Jesus died.

The panel is made of well-dried wood of deciduous trees, most commonly limewood. Several boards are glued together to form a single panel which is strenghtened by transverse braces placed in “dovetail” slots. It is essential that braces be made of harder wood than the panel itself.

An icon often has a several milimetre deep recess, with a 2-5 cm margin from the panel edges. This shallow recess is called the kovcheg or ark, and is the divine part of an icon. The outside margin is called the polya and refers to the earthly world.

2. Canvas

In the next step the canvas is glued to the panel so that the support is elastic and the painting layer is protected from cracking.

Hot glue obtained from rabbit skin or other animal skin is used – the materials should be as natural as possible. Using the canvas also has a particular theological rationale – the first icon, not made by human hand, was the reflection of Jesus Christ’s face on canvas (St. Veronica’s Cloth).

3. Levkas

Levkas is the glue-and-chalk ground used in panel painting and gilding.

It is obtained from Champagne chalk and rabbit skin glue. Levkas is applied by brush strokes in twelve layers in a crisscross manner. This is a theological reference to the number of Apostles.

When the ground is completely dry, the icon is thoroughly polished to full smoothness.

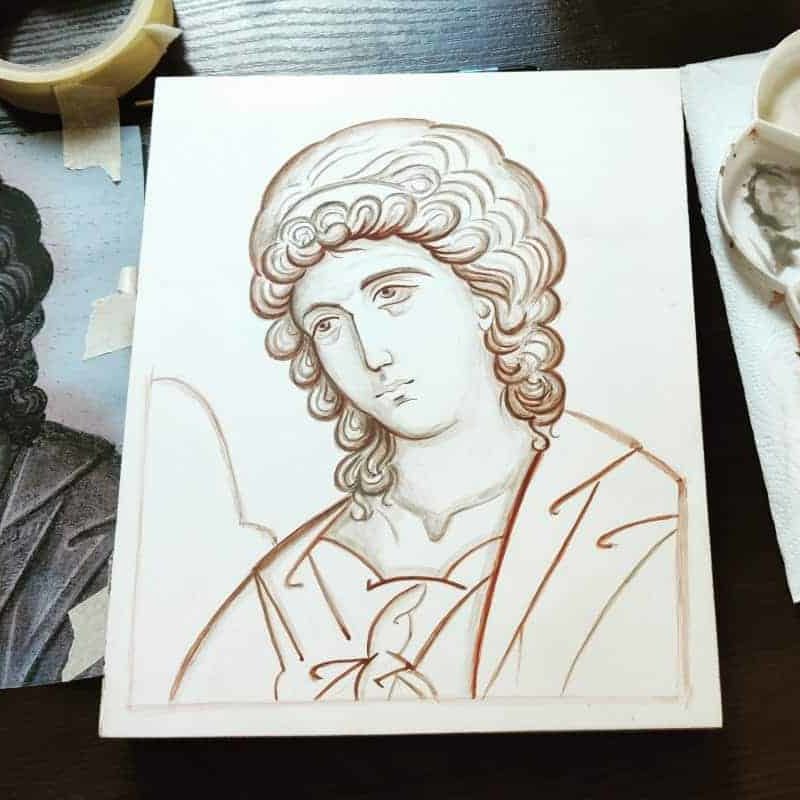

4. Drawing

Before gold is applied, a sketch of a biblical character or scene is made on the icon.

Main lines should be then delicately engraved with a stylus/engraving pen so that the sketch is not lost during painting.

Every holy figure or genre scene has their own specific accompanying details with which they are traditionally depicted. They can be found in special templates or guides called “podlinniks” (sing. “podlinnik”). Those traditional details should be preserved so that the icon retains its universal, i.e. iconic character.

Reverse perspective, also called divergent perspective, is a form of drawing specific for icons. It places the viewer in the central point, somehow making the icon a “window to eternity”. The drawing is composed in a way which makes an impression of viewing from various points. This perspective deliberately makes the painting look imperfect, awkward, even naïve, in order to highlight that certain planes are on a higher, spiritual level.

Figures are often depicted in a larger scale to make them look more significant.

5. Gilding

The gold of holy figures halos or the whole background reflects the heavenly light which personifies the presence and holiness of God.

Hence every holy figure depicted in the icon and surrounded by a golden halo shows the divine glory suffusing his or her soul.

Gold is applied on an icon using various techniques. Water/poliment gilding with burnishing and and oil (mixtion) gilding are most commonly used.

The water/poliment technique is considered more sophisticated. The clay (poliment, usually Armenian bole) is mixed with a specific amount of of rabbit skin glue aqueous solution, and this warm and dilute mixture is applied in fine layers onto the gilding surface. Each layer must be dry before the application of the next one. The final layer is smoothed with a short, stiff brush or a felt ball.

This is followed by the gilding proper. A gold leaf is transferred onto a gilding cushion and divided into smaller pieces with a gilding knife. Such prepared leaves are layered on using a gilder’s tip onto the poliment surface which has been rinsed with 40% alcohol. Once the gold leaf has been glued to the surface, it is smoothed/burnished with a piece of polished agate to obtain a smooth and shiny surface.

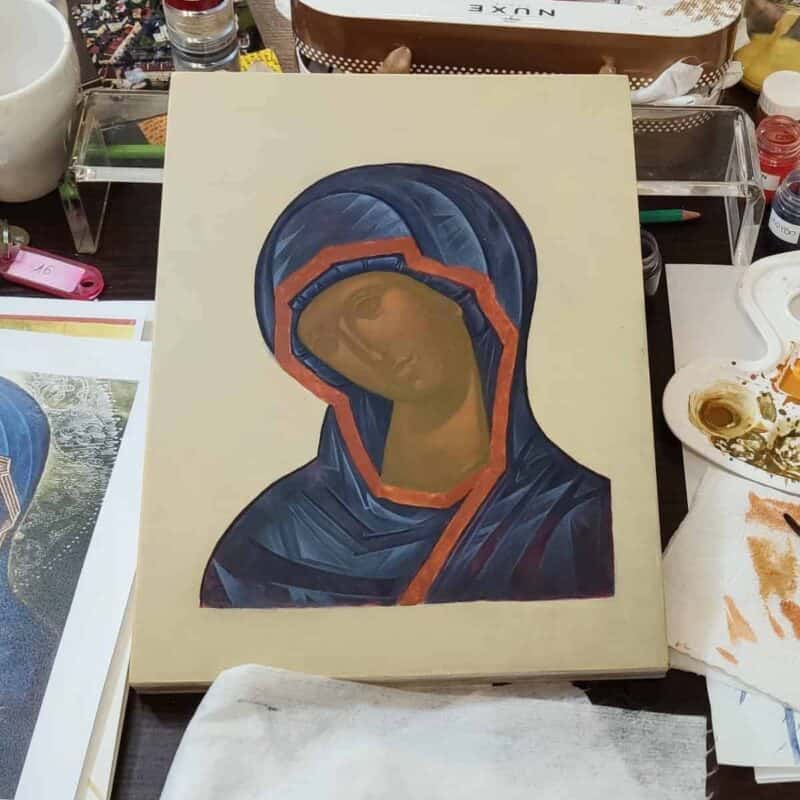

6. Painting

Icons are painted using an ages-old technique of egg tempera. Dry powdered pigments are used, usually of mineral origin.

“Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust” is what they are supposed to remind. Our earthly life is fragile, but also we are all children of the Earth.

Egg yolk mixed with dry white wine is used as a binder. A specific pigment is then added to obtain a paint of milky consistency. For most pigments, especially mineral ones, it is not enough to mix them with the binder on the palette, but they must be ground, possibly in a mortar. A respective, usually small amount of the pigment and a few drops of the binder are ground in a mortar for several minutes. Such a ground paint is diluted with the binder.

Painting an icon is a long process, requiring concentration and knowledge of respective techniques, including shading. Layering the tempera mixed with pigments begins with the darkest shades and gradually passing towards the lighter ones. The layers are applied using the glazing technique in order to draw attention to the figures. Their faces are highlighted in the final stage.

7. Colour

Colour is one of the most important parts of the iconographic language.

The colour of clothes e.g. determines the traits of a figure or its role in the icon.

Gold is the colour of divine power and light, of the Omnipotent God, His Glory, Majesty and Subtlety. It refers to the Invisible Light.

Scarlet is the colour of the clothes of kings and rulers, and also of clothes ripped off of Christ in the depictions of Crucifixion. Scarlet means the earthly power and prominence, but also the martyrdom and blood shed in sacrifice.

White is the colour of purity. The colour of clothes of angels, patriarchs of the Church, Apostles and of Christ himself. White symbolises the light which suffuses the space. White is the symbol of timelessness.

Blue is the colour of Heaven and purity. It is often used as the colour of the Mother of God’s clothes. In iconography it refers to detachment from the world, being above the earthly concerns. As a colour which goes well with white it reflects the focus on spiritual life. It is the colour of infinity.

Red and azure together form a great harmony. Their connection is therefore often referred to Christ and Mary. Red with azure symbolise the balance between the earthly and the divine in figures such depicted.

Pure yellow is the colour of truth. Turbid, dirty yellow however means pride, fornication and treason, and refers to the sulphur of Hell.

Green is the colour of spring, the plant world and rebirth. In iconography it refers to new life, spiritual rebirth and the presence of Holy Spirit.

8. Light

Icons often lack one distinctive centre of light. Different parts of an icon are lit and the lighting can be contradictory, seemingly coming from many sources.

Shapes and planes are “lit” by a specific choice of colours as well. Figures depicted in an icon also glow with divine light. In their case a halo is not enough, their faces must radiate light.

The spiritual order of portrayed figures is shown outside in austere, geometrical forms which express asceticism and holiness. The figures do not gesture but they remain in the prayer; their body language is sacramental. They are shown en face or in the three-quarters view to enable the fullest contact with them. Their eyes are depicted without eyelashes, ears have an unnatural shape and mouth is deprived of emotion, as they are not supposed to receive sensual signals, instead symbolising the detachment from earthly concerns and complete focus on the divine.

9. Inscriptions and protection

What gives a painting the iconic character are the inscriptions.

A figure or scene is determined not just by a specific depiction but also by the name of who or what it portrays. Inscriptions are placed next to the heads of holy figures, traditionally in Greek or Old Church Slavonic. As the final step, a layer of olifa is applied so that all the layers below are united an the icon is protected from the elements.